Little boy mummy from the Renaissance period could change what we know about the past

The virtual autopsy performed on a uniquely preserved mummy of an aristocratic Renaissance boy allowed us to witness a short life, though …

The virtual autopsy performed on a uniquely preserved mummy of an aristocratic Renaissance boy allowed us to witness a short life, though privileged, far from perfect.

For most of human history, the odds of reaching adulthood were half-and-half at best. There are many reasons for this (many stemming from germ theory and not understanding the concepts of not flushing directly into the river you use as drinking water), but these don’t tell the whole story. For a broader view, it’s best to examine some real-life historical ruins. A scientific team from Germany has had little luck with this kind of work in the recent past.

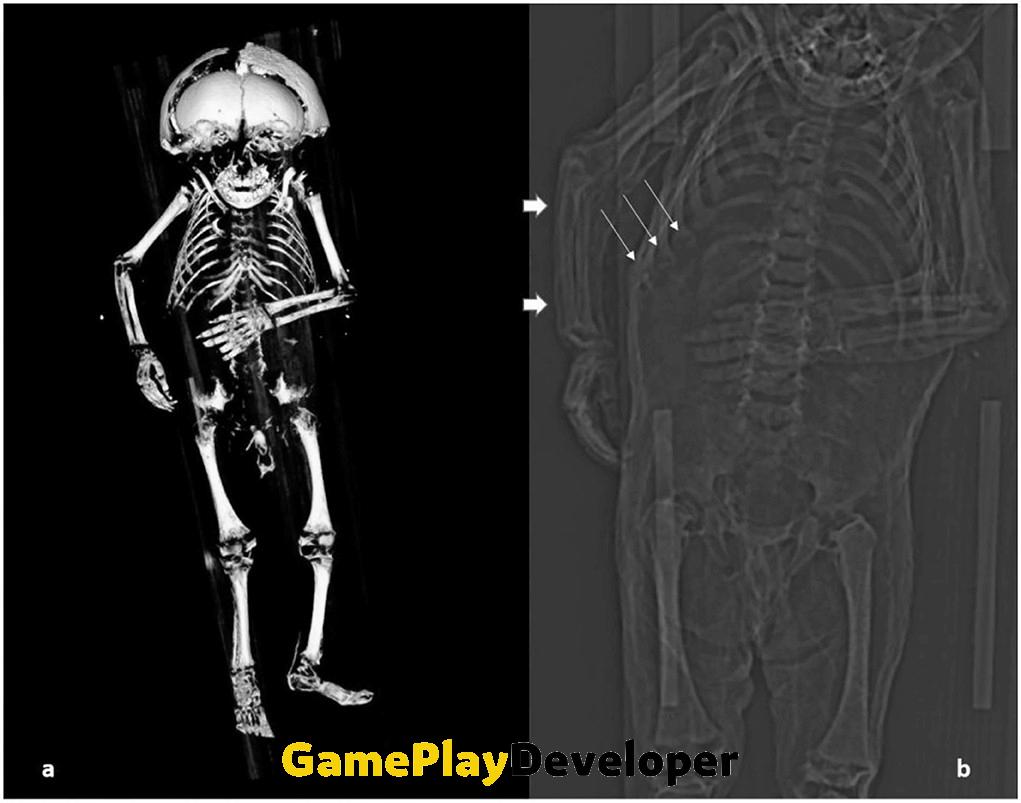

The team performed a virtual autopsy, combining the latest technology and historical archiving techniques. Teeth and bone measurements, like about a quarter of his contemporaries, revealed that the child did not exceed approximately one year of age..

He was overweight for his age and had deformities of the ribs, often observed in diseases caused by nutritional deficiencies, such as rickets or scurvy, which are almost unheard of today in those with the ability to consume fortified milk and year-long citrus fruits.

Rickets It is most commonly known as a disease that affects bones, making them soft and curved. One of the most stereotypical symptoms is a crooked-legged appearance. The little lord studied by the researchers did not have this symptom, presumably too young to crawl or walk enough to develop this appearance, but had a more disease-related feature.

Rickets can greatly increase a child’s vulnerability to major respiratory infections such as pneumonia. A 2010 hospital study found that children with rickets were more likely to have an acute respiratory infection than children without the disease. The boy’s virtual autopsy shows he is no exception: He apparently died of pneumonia-like inflammation of his lungs.

All this, according to the researchers, provides a new look at the idea of aristocratic luxury and long life. Professor of pathology at the Academic Clinic Munich-Bogenhausen and lead author of the new paper Andreas Nerlichin his statement, ” the combination of obesity with a severe vitamin deficiency, combined with a mere overall ‘good’ nutritional status almost complete lack of sunlightcan be explained by” he said and continued: “ We must reconsider what we know about the longevity of the high aristocratic infants of previous populations.“So it seems possible that many of the aristocratic babies of that time never saw the sunlight.

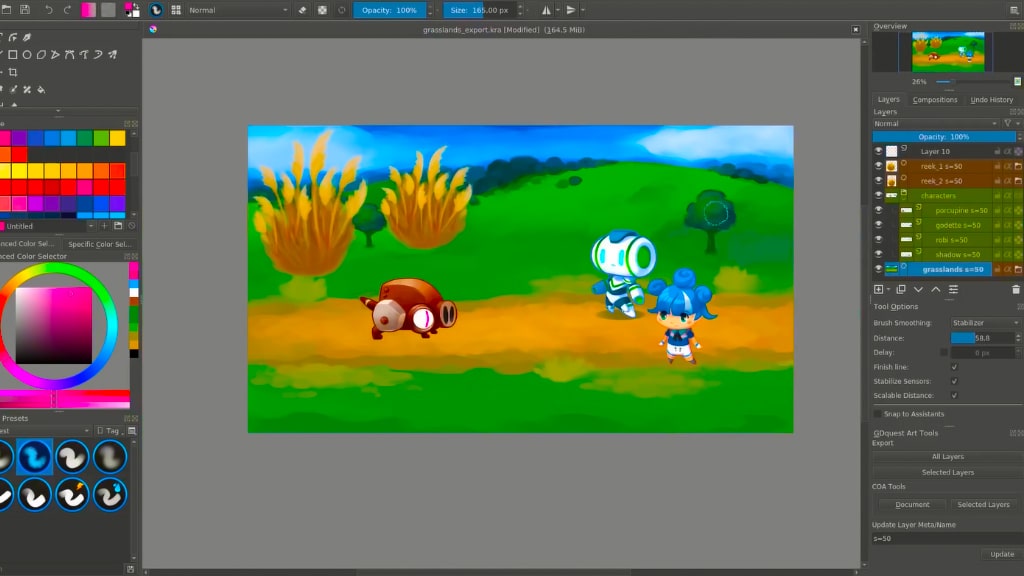

These discoveries came thanks to a CT scan. This would not have been possible had it not been for a rather unusual set of conditions that led to the natural mummification of the tiny body. While the riddle of why he died has been solved, little is known about who the boy was when he was alive.

There were mysteries about his identity to be solved. The boy was buried in a plain wooden coffin, in which his name was not written. In fact, this coffin didn’t even look big enough for his body. He was the only one buried in this manner; all other tombs had elaborate metalwork that was recorded to remember the names of the deceased for posterity.

So presumably the small body wasn’t about someone worthy of being remembered. He was also the only baby buried in the crypt. This crypt is a tomb of nobles, a dynasty of imperial counts and princes, whose origins date back to the 12th century. used exclusively by the von Starhemberg family.

Analysis of his clothes showed that he was wearing a long, hooded coat made of precious silk inside his understated box. So, as Nerlich points out, an obvious level of “special attention” could have been given.

While these clues may seem contradictory at first, when combined with radiocarbon analysis that dated the remains to mid-1635 AD, they found a possible candidate for the boy’s identity. Reichard Wilhelm, the eponymous grandson of Count Reichard von Starhemberg.

Nerlich, ” We have no information about the fate of the other babies of the family.‘ he said, and continued: According to our data, the baby was most likely the [the earl’s] first son, born after the establishment of the family cemetery.“

Learning the name and story of a long-dead child may seem like a small reward for so much scientific detective work. But it’s a result that the team believes can truly impact our connection to our ancestors and their longevity.

” It’s just a case‘ said Nerlich, and added: But because we knew that premature infant mortality rates were often very high at the time, our observations may have a valuable impact on restructuring infants throughout their lifetimes, even in higher social classes.”

The study was published in Frontiers in Medicine.